- Home

- Larissa Dubecki

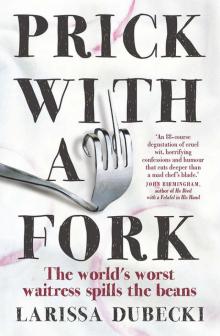

Prick with a Fork Page 5

Prick with a Fork Read online

Page 5

If Trevor represented a black hole of entropy, Felipe filled the vacuum in the High Enchilada kitchen. Maybe it was a male presence that the waitresses could talk to without gagging, maybe it was his fiancée, a sweet young thing called Mariana, who’d turn up from her own waitressing gig at the end of each night to perch at the end of the counter and swap war stories, maybe it was just that he was such a gosh-darn nice young guy who bubbled with enthusiasm for everything from soccer to sci-fi and gently chided me for smoking. He proved a rallying-point for a disparate group of individuals, from Lana the eternally cheerful cyclist to Helen the cheesecloth-wearing hippy and Julie, who spent most of her work time flogging Mary Kay cosmetics. Felipe whisked us all post-work to smoky Latin clubs on Johnston Street that felt like being transported to Santiago circa 1950. Swarthy men swung sequined women around the dance floor and the air was thick with transcontinental longing.

Surprisingly, I learned a thing or two at the Enchilada that proved to have lasting value. One evening I took a phone call from a man claiming his take-out had induced a technicolour bout of food poisoning. I knew him immediately; a table of eight guys the previous night, hunkering down near the kitchen and making halfhearted passes at me and Daisy, the little blonde waitress young enough to be flattered by their Neanderthal attentions. The only things making them sick were the bucket bongs they’d sucked down before getting the munchies. Seriously—who leaves $10 as a tip for a takeaway order if they’re not on drugs?

Food poisoning complaints are not uncommon. It’s understandable: it’s only human to want revenge as you hurl your guts up for the fifth time in an hour, and the first thing you think of is naturally going to be the last thing you ate. Notwithstanding the visceral element to food poisoning complaints (which means you should immediately distrust anyone willing to accept the offer of free food as compensation: clearly they’re frauds), it’s important to remain scientific.

So here’s the deal: if someone complains of food poisoning it’s best to adopt the brisk, no-nonsense manner of a librarian or school principal. The words ‘stool sample’ are difficult to say without sniggering, but it’s imperative that the utmost seriousness be observed during the transaction or you risk provoking the aggrieved customer.

The stool sample (don’t smirk) should be collected in a dry, sterile, screw-top container. Try not to collect urine or toilet water along with the stool; to this purpose, it’s best to urinate first before spreading plastic wrap over the toilet seat so as to catch the specimen. Once the stool sample is safely inside the sterile container, seal it then label it: your name, the date and your date of birth. Put it in the fridge wrapped in a plastic bag before taking it to your local GP for analysis at the first opportunity.

In my experience the customer will have hung up by the time you get to ‘toilet water’.

The best times at the High Enchilada were when Trevor took the rare night off to give his Mexican windcheater a rest. We could relax a little, put a different CD on the stereo. Felipe would be a whirlwind of energy at the end of the shift, making takeaway bags for all the staff to take home, hunters after the kill. Each of us would become, however briefly, the most popular person in our share house. Nachos all round! Depending on the level of poverty that week, grateful housemates might even cross your name off the cleaning roster. A symbolic act, on the whole, but a thoughtful one.

* * *

ROISIN

We needed to restock the wine shelves before service one night. There had been a delivery and we had the invoice but couldn’t find the wine. I looked everywhere and finally turned to the kitchen, wondering if it had been mistakenly put in there. The head chef told me to look in the cold room so I did. While I was looking up and down the shelves he followed me in, locked the door and put his hand up my skirt. I told him to remove it or his wife would know about it very quickly. It worked.

* * *

Things ended up going awry, as things tend to do when you’re in your twenties, with the unfathomable possibilities of life making your synapses zing with distress. Mariana started waitressing at some hippy cafe, fell in with a whole new crowd and dumped Felipe just before their wedding. He was inconsolable. It’s one thing to lose your first love, quite another to lose her to the dark forces of veganism. But things got worse for poor Felipe—much worse—when his now ex-best man took him away to Queensland. The idea was the age-old prescription for recovering from a bad break-up: a bit of sun, a bit of golf, a bit of consolatory action with persons of the female persuasion. Visiting a scenic lookout, the ex-best man took a step backwards to take a photo and fell to his death from a cliff top, Felipe looking on in horror and no doubt wanting to follow him over.

All the High Enchilada crew drifted away after that. The next floating population of pimple-faced waitresses arrived to investigate the ancient art of turning paper napkins into swans and the industrial adhesive properties of high-fat cheese. I ran into Lana more than a decade later. She didn’t remember me, by which I mean not only did she have absolutely no recollection of my name or face, she had no memory of the restaurant itself. Talk about eternal sunshine of the spotless mind. Maybe the High Enchilada era was so bad for her she simply had to blot it out in order to continue on the trajectory known as living. Maybe she’s just got a bad memory.

Don’t let me romanticise it: the High Enchilada was no picnic. But for a short while we were a happy little gang—one of those de facto urban families you read about in the weekend supplements, brought together by temporary circumstance but making the most of our fellowship at a crappy little suburban joint before life spooled out in different directions. Until this day I’ve never been able to listen to the Gipsy Kings without a stab of nostalgia, and the phantom scent of stale nachos lingering in the air.

— 4 —

LA GRANDE ILLUSION

My friend Marcus got into the waiter game for all the wrong reasons. Marcus got into the waiter game because he loves food. For him, every meal is a cause for rejoicing. Each step in the shopping, preparing, serving and eating is a quasi-religious act of homage to the thing that injects his life with its colour and elan. He savours wine like a Trappist monk who has lovingly tended the vines in the scorching heat and the freezing wind. He can spend a blissful hour in a cheesemonger, imbibing the dank aromas, the nostril-slapping barnyard essence of a really good Trou du Cru. He emerges from farmers’ markets looking like he has just witnessed The Rapture. His dinner parties—at which it is not uncommon for the food to emerge at midnight thanks to Marcus lovingly cutting the vegetables for a sofrito in a perfect brunoise and attaining the desired consistency for his curry paste only after two solid hours of mortar and pestle work—are pure torture.

Marcus wanted to work with food.

Marcus wanted to work in a restaurant that loved food as much as he did. And so he found work at a brand-new gastropub that was getting good reviews and seemed the kind of place that would be sympathetic to a young man travelling life’s highway with a washed-rind cheese in one hand and a ciabatta in the other.

It was a casual process of disabusement. Nothing fatal in itself; just small factual paper cuts that revealed the fiction behind the romantic facade of the restaurant industry. The chef did not make the gnocchi lovingly but, depending on the day, hastily, angrily or homicidally. The specials list was inspired less by what had just come in from the market and more by what was about to go off. The biggest-selling winter dessert was summer berry pudding.

Then one day there was an incident. I mean An Incident. And Marcus was never quite the same again.

It was the tail end of an otherwise uneventful lunch service. The dining room, one of the first to embrace the open kitchen (this being the 1990s and all—history relates that Everything But The Girl’s breakthrough album Amplified Heart was playing on the stereo), was empty save for one last table that was starting on coffee. Marcus was left manning the floor alone while the sole chef left on duty began a cleaning frenzy (‘quite out of character’

, the record notes). The four remaining diners, all expensively dressed, were sitting at a table nestled underneath a broad ledge created when a hole was punched through the wall separating the rear of the dining room from the kitchen. As well as providing a then-novel insight into the workings of a commercial kitchen, it also provided a handy shelf for corks, wineglasses, and the olive oil kept for drizzling on pizza and salads (remember this was the 90s—drizzling was de rigueur).

Perhaps inevitably during the chef’s uncharacteristic cleaning frenzy a bottle of this olive oil was tipped over Expensively Dressed Woman No. 1. Perhaps just as inevitably, she was extremely distressed at the re-creation of the Exxon Valdez disaster on her white silk top.

The chef activated his emergency plan and pulled a swift disappearing act, leaving Marcus to deal with the fallout. And being a young man who appreciated good food, he tried to placate the woman in the only way he knew how.

‘When I saw the green tinge I knew it wasn’t any old olive oil—it was extra-virgin olive oil, the greener the better as we considered at the time, which we used to drizzle on everything,’ he recounts sadly. ‘So I tried to draw attention to the fact that we were a quality establishment and that if we’re going to spill anything on our customers, at least it’s the real deal. And here’s the rub: I say something about how her white silk top really allowed the quality of the oil to shine through; she should have been glad it happened. Now she knows we don’t skimp on ingredients. You know? It’s not that bad . . .

‘Anyway, she’s outraged and demands to see the manager. I wish. None to be found. So I give her a business card and promise we’ll sort everything. It turned out she was pretty high up working for the premier of Victoria and she wrote to my boss on state parliament letterhead demanding that he sack me. And he wanted to sack me, of course. He was furious about having to pay for this woman to buy a new top, which wasn’t my fault in the first place, and he was furious about having this well-placed woman pissed off with the whole establishment. I kept my job in the end—I guess because it would have been too much effort to find a replacement, but to this day I feel like I was thrown under a bus. I guess my main solace is remembering that she obviously didn’t like food that much. Her loss.’

* * *

RICHIE

I was standing at the counter one night and an incredibly good-looking woman sashayed out of the toilets and came up to me. She was totally hot. Supermodel hot. And she asked me, ‘Are you the manager?’ and when I said yes she started stroking my face really gently and looking at me with come-fuck-me eyes. I’m just standing there like an idiot, but like I said, she was hot. And finally she stuck her index finger in my mouth and said in a really sexy voice, ‘I’d just like to tell you there’s no soap in the women’s bathroom.’

* * *

A sorry tale, is it not? One man’s soft-focus view of the restaurant world, destroyed by callous indifference towards its worker bees. Do take heed. There are lessons to be learned.

A forensic examination reveals Marcus was unwittingly caught in a classic pincer movement between the chef, who refused to own up to his mistake, and the owner, who valued his chef above his waiter. Surprised? Don’t be. If the workforce of a typical restaurant can be considered a pyramid, then chefs are at the tip while waiters comprise the huddled masses at its base.

Or imagine the workings of a restaurant as a game of chess. The owner would be the king, the chef the queen, the sous and pastry chefs rooks, the sommelier and floor manager bishops, the waiters a whole pathetic bunch of expendable pawns. They come, they go. They’re more or less interchangeable. A good waiter—not quite up to the standards of a maître d’ but a professional journeyman nonetheless—might reach the status of a knight in our chess analogy, but knights are easily harassed and destroyed by pawns. Go figure that one out and get back to me.

Waiting tables during the good times can be extremely rewarding for the lover of food, as Marcus discovered. When time is ample and customers appreciative, one’s knowledge of sourdough culture, fleur de sel sea-salt and the taste benefits of hanger steak over the more celebrated eye fillet are a delight to share. A good waiter will concoct a little conspiracy with the customers in which they giggle over the deliciously fattening triple-cream cheese like school kids who have just heard the word ‘tits’. When times are good, a waiter will woo, and be wooed in return.

When the atmosphere is stressed, the customers hostile and time a rare commodity, it is the wise waiter who operates under the assumption an invisible target is painted on his back. This target might as well be painted in luminol (the chemical compound that glows blue in the presence of blood; you’ve seen it on CSI) because if there is blood to be spilled it is the waiter’s. Does it matter if he was the person responsible for the lost order docket, the forgotten martini or the steak that was rare instead of medium-rare? No, it does not. In the bastardised game of pass-the-parcel that constitutes the average dinner service, the music always stops on the waiter.

When something punishable by sacking has occurred, the owner’s mind will be a frenzy of rationalisation. He’s itching to sack someone, if only to assert his authority over the staff, to SHOW THEM WHO’S BOSS, but who will it be? A chef? Where is he going to find another chef at short notice? He could always call an agency, but agencies are expensive and they’re typically staffed by chefs whose anger management and substance abuse problems prevent them holding down a regular job. Anyway, it was all the waiter’s fault. Yes, yes, it was definitely the waiter’s fault. Sack the fucker!

The problem leeches directly from the fact that, unlike the chef, the waiter requires no formal training. This breeds contempt. ‘That waiter . . .’ thinks the owner, ‘that waiter is fucking useless. My five-year-old could do the job just as well. No, my five-year-old could do the job BETTER.’ It’s yet another example of a valuable skill-set being reduced to the possession of two arms, two legs and a beating heart.

Despite this sorry state of affairs, waiters such as my friend Marcus are in thrall. Good food and fine wine for the many, many others like him start out as a hobby and quickly degenerate into a chemical imbalance. Such waiters enjoy a fatal symbiosis with the industry that employs them. In their time off they’re likely to be found spending all their spare dough, then dipping into their rent money, on lushing out over lunch and dinner and quite possibly brunch and supper as well.

It’s hard not to be sympathetic. It’s an injustice to possess a tourist visa to the world of food without the funds to actually live there. The push-pull between desire and means is acutely painful. Anyone paid to watch people wash down pristine oysters with French fizz inevitably thinks, ‘Hey, that looks good. I must get me some of that.’ It’s human nature.

George Orwell had a bit to say on this matter. It’s no coincidence that Down and Out in Paris and London, an account of his year living with the downtrodden—in, yes, Paris and London—features a lengthy episode in which he toiled as a dish pig in a hotel restaurant. The view from the sink was not good for old George. He was rancorous towards waiters transported by the spectacle of the dining room. He was poisonous towards anyone deriving pleasure by proxy. In Orwell’s eyes the chef was a bastard—fair enough—but the waiters were no more than restaurant Uncle Toms. They were the worst of the worst: sycophantic house slaves in awe of their masters.

Over to you, George:

The moral is, never be sorry for a waiter. Sometimes when you sit in a restaurant, still stuffing yourself half an hour after closing time, you feel that the tired waiter at your side must surely be despising you. But he is not. He is not thinking as he looks at you, ‘What an overfed lout’; he is thinking, ‘One day, when I have saved enough money, I shall be able to imitate that man.’ He is ministering to a kind of pleasure he thoroughly understands and admires . . . They are snobs, and they find the servile nature of their work rather congenial.

NO! No, no, no, no, no! All due respect to the man who gifted the world 1984 and clocks striking thirte

en and all that—but to suggest a waiter watching diners stuff themselves after closing time is simply admiring the cut of their jib is patently false. That waiter is not thinking fondly of the fine meals he will enjoy one day, God or Lotto permitting. He is full of bitter, pustular hatred towards the people who are not only keeping him from his knock-off drink but have also exposed him to the wrath of the chef by bullying him into taking the order with the classic line, ‘We’re friends of the owner.’

And so what if the waiter occasionally likes to reward himself with a little foie gras, a little Châteauneuf-du-Pape? To stick to terms Orwell might appreciate politically, let’s reconfigure it as ‘equal restaurant rights for all’. Up the revolution.

Finding a place of employment that does away with the problematic matter of chefs altogether is a Pyrrhic victory. It means joining the waiter sub-class better known as fast-food workers. A direct route to oblivion. The minute you pin on that name badge you cease to exist as an individual. A paradox, you say? Submit your complaint on company form 12A.3 to the human resources department. If you haven’t heard back from us by the end of next year, feel free to follow up with a phone call.

Prick with a Fork

Prick with a Fork