- Home

- Larissa Dubecki

Prick with a Fork Page 4

Prick with a Fork Read online

Page 4

The inner dialogue has plenty to say in such a situation. In fact it’s babbling incoherently. ‘And you call yourself a feminist!’ ‘But I need the money.’ ‘It’s degrading and these men smell like cheap cologne.’ ‘Why didn’t the ad say I needed to be open-minded? Isn’t that code for strippers?’ ‘Can’t stripping be an empowering act?’ ‘Oh god, what would Germaine Greer do?’

While the men cheer an objectively impressive display of flexibility—one of the women touches her toes as if she’s hinged at the waist—I decide Germaine would stick it out for the rest of the shift. Even feminists need to pay their rent. I’ll get tonight’s pay, go home and call an emergency meeting of the sisterhood to discuss the problem in depth.

Performance over, the beaming crowd of men trudge up three flights of stairs to the function room, where tables are laid out for their power dinner: rib-eye, the steak of choice for the red-blooded bogan, and many, many more of the second-cheapest bottles of cabernet. They eat. They drink. There are speeches and awards. Maaaate. Then the lights once again go low, and a song booms through the audio (Bobby Brown’s ‘Humpin’ Around’, which makes much more sense thematically) and—quelle surprise!—three different near-naked women bounce out like the presenters of Nude Aerobics Oz Style. ‘Why do they need new strippers?’ Felicity whispers as she passes with a tower of gravy-smeared plates. ‘Were the other ones broken?’

Captivating though the floorshow is, there’s work to be done. Schlepping trays up and down stairs to the ground-floor kitchen is pretty aerobic in itself. It’s exhausting, sweaty work, which perhaps explains why I lose concentration for a nano-second—just long enough for an opportunistic steak knife to break free from the urgent cluster of silverware heaped clumsily on my tray. It slithers to the edge and—I swear this all happens in slow motion while I struggle desperately to prevent another two dozen following it in sympathy—takes a suicide leap over the balustrade. It spears downwards at a terrifying angle, and after what feels like an eternity I hear it clattering on the terracotta tiles three floors below. The sound echoes up the stairwell, hideously amplified for everyone in the building, and quite possibly the greater central business district, to hear. So does the female voice, pitched upwards by shock. ‘Oh. My. Fucking. God!’

And that’s how I lost my second, short-lived waiter’s job, when I nearly killed a half-naked stripper with a sharp knife. True story.

— 3 —

DOWN MEXICO WAY

Six easy folds are all that stand between a 20 × 20 centimetre two-ply napkin and a graceful paper swan. I could go into more detail but the sun appears to be setting on the origami serviette. Once a staple of the restaurant dining table, it’s now sighted only rarely, usually staging brave guerilla skirmishes alongside the single pink carnation in outer-suburban Chinese restaurants.

The first job of the evening was to arrange the swans—in red, green and white, the colours of the Mexican flag, olé!—in wineglasses; not delicate crystal but clunky things cunningly designed to withstand dropping on hard surfaces, temperatures of up to 500 degrees and all-out nuclear Armageddon. If the bomb ever dropped on Melbourne, the only things left standing would be cockroaches and the Mexican Casa’s stemware.

You know how Mexican food has become hotter than a jalapeno, the cuisine du jour for a certain demographic with their beards and tattoos and deep, almost subterranean irony that no one else can really understand, man?

No. Not like that.

The Mexican Casa was so old-school it made franchise chain Taco Bill’s look like the final word in cutting-edge cool. It predated the fashionable new-wave Mexican by several thousand light years. In terms of gustatory fashion, it was pre-Columbian. Actually, that’s not going back far enough. It was positively pre-Lapsarian, although there’s room to argue that diners carving their initials and the odd expletive into the wooden placemats were an early precursor to the social media revolution. But truth is, if there was ever a crowd mooching impatiently around outside this joint on a weird retail non sequitur of a street—a mechanic next door; an office stationery supply across the road—it was because the fire alarm had gone off thanks to a plate of nachos catching fire in the dodgy oven.

To its customers it was the Mexican Casa but to its disaffected band of novice waiters it was more commonly known as the High Enchilada. Susie, another high school friend, got me the job with the promise that inexperience in Mexican food was no barrier to employment here. Right she was, too. The hiring process was based on a completely different set of criteria. Only in hindsight did I detect a certain pattern in the gender of the floor staff. All female. No exceptions. The policy can be traced in a direct line to one half of the owners, a porcine slob named Bruce with a weak chin, a massive gut barely corralled by his trademark striped polo shirts and a fondness for the genial sexism of the middle-aged man.

‘You know why men like to hold doors open for women?’ he’d ask while holding the door open and looking skin-crawlingly pleased with himself (quite an impressive feat, incidentally, while wearing Stubbies shorts). ‘So we can look at your bottoms when you walk in front of us. You don’t think men are so stupid to do something for nothing, do you?’

Listening to Bruce’s proselytising was an unspoken part of the job. Bruce had plenty of wisdom to share, most of it revolving around the tortured age-old questions of male–female relations and why women are far happier when fulfilling the noble role of homemaker, even if they don’t realise it thanks to the lies of feminism. Creepy, yes, but pathetic, more. You quickly got the feeling he wasn’t the kind of guy who was listened to unless he had a captive audience being paid ten bucks an hour under the table, no questions asked. He was snatching his moment in the sun—a sexist sensei teaching the ways of the world to a bunch of post-adolescent girls.

Women’s bottoms aside, Bruce’s main topic of conversation was his infant son. I can’t remember the boy’s name, mostly because Bruce habitually referred to him as ‘the little fella’. It was a sweet-sounding verbal idiosyncrasy—in fact, it seemed the only thing going in Bruce’s favour until it was pointed out that no one had ever met Mrs Bruce or Bruce Junior. This added weight to Susie’s theory that when Bruce talked incessantly about ‘my little fella’ he was in fact referring to his dick.

‘My little fella’s just amazing,’ Bruce would announce apropos of nothing while slicing the top off a 10-kilo bag of pre-shredded yellow cheese. ‘My little fella’s growing up fast,’ while stacking caterers’ tubs of sour cream. Or, horrifyingly, ‘Gosh, you should have seen my little fella this morning.’

Bruce had gone into business with a fellow named Trevor. Bruce made Trevor look only moderately offensive. Trevor was a mouse of a man with a silken blond moustache left over from the set of Semen Demons 4 and big, weepy blue eyes. He was the guy who had sand kicked in his face at the beach by the guy who had sand kicked in his face by the other guys.

Their background had nothing to do with hospitality. Bruce had been an advertising rep; Trevor was a teacher. In a similar vein to the three-year-old who announces she wants to be a hairdresser in outer space, they decided it would be a brilliant idea to open a restaurant.

It was the usual story. They wanted to be the captains of their own destiny. To break free from the shackles of the wage-slave working in a corporate chain gang and waiting anxiously for payday every second Thursday. In reality, they shared a fate similar to many restaurateurs in that they essentially bought themselves a job. A seven-day-a-week job of unsociable hours and the ineradicable perfume of stale nachos. The High Enchilada turned out not to be the road to riches but the unsaleable coffin of two men’s dreams of a better, self-actualised life. They might have thought they were being clever by opting for Mexican—essentially, a bunch of pre-prepared components thrown into the oven to heat, melt and generally deliquesce into protein-and-cheese pap—meaning they needed no actual chef. Instead they ended up being tied to a tiny, overheated, unventilated kitchen hardly bigger than a double fridge

.

Clearly the marriage wasn’t working out. The tension between the two was palpable. Bruce and his impressive gut lorded it over Trevor, who only inflamed the situation by responding with the affronted dignity of a 1950s housewife whose husband hasn’t come home straight after the game. Front of house it remained the same desultory joint serving the same desultory slop; backstage it was like the Kramer vs Kramer theme restaurant. It was a relief to everyone when they stopped working together, taking a financial hit they could barely afford, doing one night on, one night off, and each prodding the waitresses for gossip about the other while pretending not to care.

Like childbirth, waiting tables is one of those activities that’s meant to come naturally. You get people food and drinks and you clear everything away when they’re finished and it’s just so freaking obvious, isn’t it? Except it’s not. Expecting people to know exactly what to do the minute they pick up an apron is like expecting a Lord of the Rings fan to know what to do in case of orc attack or someone who once watched Grey’s Anatomy to perform a tracheotomy using a Stanley knife and the tube from a ballpoint pen. You don’t pick up this stuff by osmosis. Despite the extensive experience I boasted about to Bruce and Trevor at what passed for an interview (Bruce looking at my bum; Trevor looking like he was about to burst into tears), I still had my L-plates on. I made ridiculous towers of plates and served from the left and leaned across people and interrupted conversations and started clearing before everyone at the table was finished. No one tells you not to do that stuff. Not at the places where I worked, anyway. And not that it mattered at the High Enchilada, where an evening’s service was considered a success if no one was maimed.

* * *

VINCENT

It was a really busy Friday night when one of the men’s toilets stopped working and I had to investigate. I found a pair of boxers stuffed in the cistern. Someone had shat themselves and instead of going home they’d ditched their undies and gone back out to drink at the bar.

* * *

Another important thing for the junior waiter to learn—you have to decide early on what type of waiter you’re going to be. It’s as crucial as it is urgent. The concrete is setting. You’ll be frozen in that attitude forever. Fixed as if by superglue. I tried the sassy bartender: ‘Wad’ll it be?’ I tried the blowsy American diner waitress: ‘Want some more coffee, hon?’ But the truth is even less glamorous than imitating a twice-divorced bottle-blonde named Valerie.

There is a modern school of thought that having to be nice in the line of duty has become the exclusive domain of the less privileged. Mandatory smiling is a sign of the underclass. Service industries that expect their employees to put on a veneer of friendliness force people to sell their very humanity; it’s yet another one of capitalism’s little jokes on poor people. But tempting though it is to wrap myself in the comforts of that philosophy, the truth is closer to the German notion of schadenfreude—otherwise known as taking pleasure from other people’s misery (the classic example involves seeing a new-model Mercedes reverse into a pole). The default setting for waiters like myself flips that concept into freudenschade—taking misery from other people’s pleasure. Sad and pathetic though it may be, I’m the sort of person who bitterly counts down the days until friends return from holiday. They’re jumping on a plane right now; economy class; it’s going to be hell, I think with satisfaction after spending two weeks torturing myself with images of my loved ones lying on deck chairs never more than a few metres away from the nearest cocktail. With an attitude like that, what chance did any of my customers stand when they decided to treat themselves to a nice meal out?

And even though it was willing to hire someone with virtually zero experience, a place like the Mexican Casa, with its idiot bosses and schlubby diners, was a dangerous place for someone with a naturally glass-half-empty disposition.

The concrete set. And as a waiter I was stuck in a freudenschade attitude forever more. Frozen, like the Little Match Girl, minus the sweetness and the sympathy.

I’d never experienced the joys of putatively ‘Mexican’ cuisine before I started working at the High Enchilada. I was bewildered by the plates of variegated slop, beans barely distinguishable from meat and everything striped with the tri-colour of salsa, sour cream and guacamole. With my two decades’ worth of wisdom, I figured the customers would be, too. My line when delivering food to tables, until Susie overheard and made me promise never to repeat it again, was ‘I know it doesn’t look very good but it tastes okay’. Hindsight reveals I might not have been scaling the heights of customer service, but standards weren’t so high in a place where diners were known to request cravats of water.

Back in those days Mexican food really meant Tex-Mex, which translates as something no Mexican national would recognise as a food substance. Like nachos. You know the story about nachos? In 1943 a bunch of American army wives arrived at a hotel in the Mexican town of Piedras Negras, just over the US border, after the restaurant had closed for the day. The considerate manager, Ignacio ‘Nacho’ Anaya, threw together what he found in the kitchen that day: tortilla chips, cheese and jalapenos. He cut the tortillas into triangles, grilled the cheese on top, and added the jalapenos. Hey presto, a legend was born.

It’s quite possibly apocryphal, but I like this story. I like the way a supposedly ‘authentic’ Mexican dish came about through a few kitchen offcuts being thrown together for a bunch of cultural outsiders who didn’t know any better. It’s an accident of a dish. More Texican than Mexican. An edible car crash. If Ignacio really did go on to open his own restaurant, I hope he laughed all the way to the bank.

Nachos sold their socks off at the Mexican Casa. We even planted a little paper Mexican flag on a toothpick in the top, just to drive the whole authenticity thing home. I lost my taste for them pretty quickly. If you’ve ever had time to observe the consumption of nachos, and I had ample opportunity, they are in the title-fight for the world’s most disgusting dish. The problem is that they’re meant to be shared, and nine out of ten people faced with a plate of nachos will go in with fingers rather than cutlery. This is fine on the first layer, where you can pick off individual corn chips without too much trouble. But excavate down to the second layer and you quickly run into a primordial swill of cheese and salsa, with guacamole and sour cream making their own contribution to the toddlers’ pool gloop. What people generally do when eating through this stage is dip their digits into the gunge, rummage around, tear off some fast-collapsing corn chip, then lick their fingers before they go in again. Dip, dip. Lick, lick. It’s an epidemical crisis just waiting to happen, and I’m not willing to be Patient Zero.

Nachos aside, the menu soon revealed an easy to grasp pattern. Tacos were fried corn tortillas filled with beef, beans or chicken. Taquitos were rolled, fried corn tortillas filled with beef, beans or chicken. A tostada was a flat, fried corn tortilla covered in beef, beans or chicken. An enchilada was a soft corn tortilla rolled around beef, beans or chicken. A burrito was a super-sized enchilada. Fillings? Beef, beans or chicken.

When UNESCO added Mexican food to its list of the ‘intangible culture of humanity’ in 2010, it was not thinking of the Mexican Casa’s menu.

Nonetheless, authenticity—or a simulacrum thereof—was a big thing for Trevor, who eventually bought Bruce out of his share for the price of a second-hand family sedan. A great relief all round. ‘More time for Bruce to play with his little fella,’ Susie snorted. The upshot of it was that Trevor now manned the kitchen alone seven nights a week and his big, weepy blue eyes were weepier than ever.

This was a man who had never heard of a mole, and would have simply looked confused and weepy at the notion of putting chocolate into a savoury dish. As far as I could tell, the kitchen had never come into contact with chipotle, the smoked chilli that gives so much Mexican food its thrilling, smoky backbeat. Trevor’s version of authenticity was to repaint the dining room in pale pastels the colour of nausea. Festive sombreros were hung from the ceilin

g. To drink there was Mexican punch, which was equal parts raspberry cordial to pineapple juice with lemon slices floating on top. Margarita glasses came crusted in sugar instead of salt. Mexican rice was dotted with red and green capsicum. Dessert was Mexican crème caramel, made with Kahlua. Mexican coffee—with a splash of Kahlua, naturally—was made in one of those drip-filter numbers that were big in the 1970s, until Trevor finally splashed out on a domestic espresso machine and celebrated by pasting ‘Now . . . with Cup-of-Cino!’ signs around the dining room.

The place owned two CDs: the Gipsy Kings’ self-titled album and the Pretty Woman soundtrack. The Gipsy Kings were for the busy period. A bit of ‘Bamboléo’ action: make people eat faster, drink more, keep the mood upbeat. ‘Psychology,’ Trevor would nod sagely as though he was at the cutting edge of behavioural research. Pretty Woman was for pack-down, when the mood was getting sleepy and you just wanted the last of the nacho bandits to get the fuck out and let you go home. Roxette’s ‘It Must Have Been Love’ was just the ticket.

Like I said, authentic. While never having visited Mexico, Trevor was the proud owner of a Mexican-themed windcheater that he’d pull on before heading out to do the old customer meet-and-greet. To put it politely, it had seen better days. Indelible sauce stains merged with the Aztec writing; the cuffs were a delicate shade of greige. ‘I really hope he doesn’t put that on just for us,’ a woman sniffed witheringly one night after Trevor had done the rounds with all the self-importance of a three-star chef-patron.

For a while after Bruce left, Trevor was like the sole survivor of a shipwreck in a slowly sinking lifeboat. I had no respect for the man but it wasn’t enjoyable. It was like watching your fourth-favourite cat suffer from scrofula. But then Trevor made the decision that saved him. He decided to employ an apprentice. It was a cruel move, really, to pay measly first-year apprentice wages for a seventy-hour week, with no tangible educational benefit that would put the victim-candidate on the path to fine dining. But along came Felipe, the Chilean soccer fanatic. Even aside from the fact that something about the cast of his mouth made him look endearingly like a Mexican walking fish, he was a shoo-in for the job. Mexico and Chile are separated by 7300 kilometres and entirely different food cultures, but that wasn’t going to stop Trevor bragging to the regulars about his authentic South American chef.

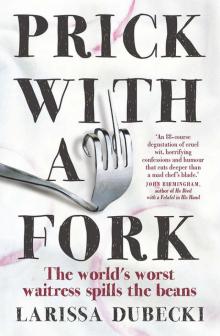

Prick with a Fork

Prick with a Fork